This article is published in collaboration with the Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia.

This is the decade of change. The COVID-19 pandemic, recent geopolitical conflicts, climate change, have pushed us to think about the greatest challenges of our time and reassess the ways in which we do things. The education system needs a hard look, too.

While the term "inclusion" has surfaced as a megatrend across public and private sectors in the last couple of years, it is no stranger to the world of education. What is new however, is the realization by governments and civil society that inclusive education involves more than simply placing a student with a disability in the classroom. Many education systems claim to be inclusive but are instead following either segregated or integrated models, missing the mark on meaningful inclusion.

Striving for meaningful inclusion

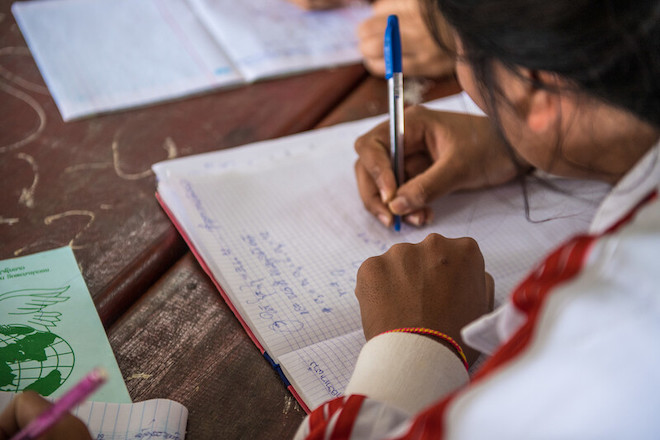

Inclusive education requires systems change, one that stems from a change in mindsets and skillsets to foster a sense of belonging for all students in the classroom. Systems change requires principles of inclusion such as whole-system inclusion, the role of learning-friendly environment, how to adapt a curriculum to student needs, differential learning, and universal design for learning, amongst others. The UNICEF report, Education for Every Ability (2020), offers entry points for practical improvements in each of these domains.

Students with disabilities who are included in school are healthier, can apply their skills to other settings, look forward to going to school, and are more likely to be civically engaged and employed later in life. Students without disabilities have much to gain too, including broadening their perspective taking skills, opportunities to collaborate in creative ways, and understand first hand, the process of inclusive community building. These are just some of the reasons we need to make a change now.

International reports suggest that are about 43.1 million children (0–18 years of age) with physical and/or intellectual disabilities in East Asia and the Pacific (UNICEF, 2021). Many of these children do not attend school at all and are vulnerable to entering the informal job market, child marriage, and experiencing exploitation, violence, and poverty.

While school closures from the COVID-19 pandemic have caused devastating effects on student learning, the move offered us an opportunity to think about meaningful inclusion in schools. School closures have affected a staggering 140 million students in Southeast Asia and 260 million students in East Asia (UNICEF, 2021). UNESCO estimates that at least 2.7 million children will not return to school, in addition to the 35 million students in East Asia and the Pacific who have dropped out (Hulshof and Tapiola, no date). Students with disabilities are more likely to remain out of school once schools fully reopen, which can perpetuate a cycle into poverty.

It is true that all 10 ASEAN member states aspire to create inclusive education systems for students with disabilities shown by their commitments to international, regional, and national frameworks these ambitions, but they can struggle to make progress on the ground.

Addressing challenges

Challenges in making progress are abundant, but those same challenges lend themselves to innovative opportunities. For example, even before entering a classroom, a medical model diagnosis is limited in its ability to present a student’s strengths and weaknesses in the learning process and may lead to a segregated intervention and education planning. This challenge has sprouted the need for a functional approach to data collection. The Washington Group/UNICEF Child Functioning Module identifies children who have difficulties that can hinder learning by understanding varying degrees of limitations in their functions as interactions with the environment. A disability is, after all, a barrier between a person and their environment, and this module shifts our thinking to see this connection more clearly.

Another fundamental challenge lies in the heart of the education system—teacher training. High quality and consistent pre-service and in-service teacher education remain fundamental for inclusive education. Funding, political will, and incentives for teachers can support this cause.

Finally, a country’s leadership has the power to set the tone for a cultural shift toward inclusion. Leaders must be inclusive themselves, publicly use inclusive language, and advocate for the human rights of all their constituents, including those with disabilities.

In summary, inclusive education is necessary at all levels of education, from preschool to post-secondary school, in technical and vocational training. It is an agent of change to encourage lifelong learning and full participation in social, economic, and political life. Inclusive education is not just for students with disabilities but can offer transformative learning opportunities for all students to build an inclusive, more resilient society.

References:

- ASEAN (2015), ASEAN 2025 Forging Ahead Together. Jakarta.

- ASEAN (2020), ASEAN Comprehensive Recovery Framework. Jakarta.

- ASEAN (2020), Implementation Plan: ASEAN Comprehensive Recovery Framework, 2020. Jakarta.

- CAST (2018), Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 2.2. (Accessed 10 May 2022.)

- Hulshof, Karin and Tapiola, P. (no date), It Is Time To Reopen Southeast Asia’s Schools. (Accessed 5 April 2022.)

- Inclusion International. (Accessed 5 January 2022.)

- UNICEF (2017), UNICEF/Washington Group on Disability Statistics Module on Child Functioning. New York.

- UNICEF (2020). Education for Every Ability. New York.

- UNICEF (2021). The Future of 800 million children across Asia at risk as their education has been severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Press Release. (Accessed 1 Feb 2022.)

This article was first published by ERIA on 8 July 2022.

Rubeena Singh

Rubeena Singh

Inclusive Education Consultant, ERIA

Rubeena Singh authored the ERIA report, Inclusive Education in ASEAN: Fostering Belonging for Students with Disabilities, which analyzes the inclusive education landscape in ASEAN amid the pandemic and provides policy recommendations to improve inclusive education systems in the region. She is currently the manager for research and knowledge at research and strategic communications agency Kite Insights.