This article is published in collaboration with Grab.

Of all the internet exports of Southeast Asia, viral memes of honking buses was probably one of the most unexpected. In 2016, when Indonesia introduced new public buses with unusually melodious horns, kids recorded the cacophony and posted them online. They became internet hits, even briefly taking over the international dance-music scene.

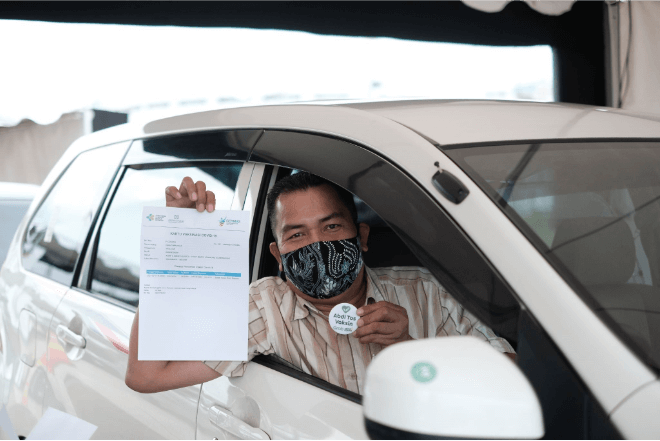

On Indonesian roads, as in many other parts of Asia, honking is an ubiquitous way for drivers to communicate. At Grab, we learned from these kinds of ingenuity, when we partnered with the Indonesian government to run drive-through vaccine centers across the country this year. While people waited in their cars for post-vaccine observation, a honk would let attending staff know that they needed help.

For over a year now, we have been working with governments across Southeast Asia to support their efforts against the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. This helps us understand the unique local needs, and combine them with our expertise in technology, operations, and online marketplaces.

Here are four of our partnerships from the frontlines of healthcare, finance, and economy.

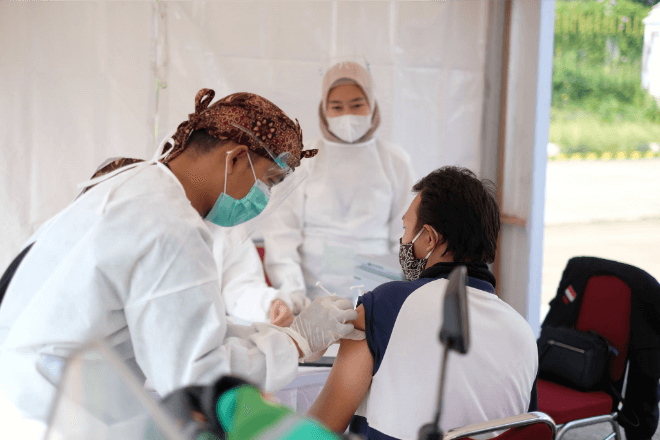

Inside Indonesia’s vaccine centers

We are working with the Indonesia’s Ministry of Health and Good Doctor, a joint venture of medical portal Ping An Good Doctor and Grab, to set up and run vaccine centers that allow drive-through for recipients on cars and motorbikes, and walk-ins. Since the launch in February, more than 100,000 vaccines have been given out across 11 centers in Bali, Banten, West Java, Palembang, Pekanbaru, Samarinda, Padang, Batam, Balikpapan, Yogyakarta, and Surabaya.

Indonesia has made it mandatory for all eligible citizens to be vaccinated and plans to vaccinate a total of 181.5 million people. At the early stages, it prioritized two groups of people: economic front-liners and essential workers in jobs with high levels of social interaction; and the elderly who were more likely to develop more severe infections.

We worked with the government to manage the entire vaccination process with digital technologies. For instance, Grab and Good Doctor invited individuals to register via the Good Doctor app. This helped shorten waiting times on-site and ensure social distancing.

Substantial effort went into linking our platforms with the government’s data ecosystem. This was necessary to ensure that registrations would run smoothly and we could also follow up with registrants on the app for their second shot.

Technology is certainly not enough. We applied our operational experience to organize the venues and oversee center operations, while the government supplied healthcare volunteers, vaccines, and medical equipment. With Indonesia’s local governments being fairly decentralized, our teams worked with both local and central agencies on venue and vaccine supply constraints.

Encouraging digital payments in Malaysia

As Malaysia emerged from various states of lockdown in June 2020, the government announced plans to provide COVID-19 stimulus to encourage individuals to spend to stimulate the economy. It announced 750 million ringgit ($180 million) of funding to be disbursed directly to people’s e-wallets.

The government’s e-Penjana scheme had a dual goal of spurring short-term economic recovery and encouraging people to use contactless payments. It chose three of the country’s largest e-wallets—Touch ‘n Go, Boost, and GrabPay—to distribute RM50 to each eligible person. Between the three, nearly everyone in the country was covered.

E-wallets ensured that these subsidies went directly to consumers and merchants, and their impact on the economy was clear. Grab’s data provides some insight. Of the RM62.5 million disbursed by GrabPay, 63% of the money was spent on local merchants to buy groceries, food, and other daily essentials. Compared to a previous disbursement, four times more senior citizens claimed their subsidies.

Part of the success of this program was leveraging on a government partnership that was already established. Malaysia had run a similar program but aimed at a relatively smaller group of users before COVID-19 hit. e-Tunai showed that e-wallets were the most efficient and transparent means to get money into pockets. When e-Penjana came around, there was already awareness and trust in the approach, and less paperwork since their credentials had been verified by the same three e-wallets during e-Tunai.

On the tech side, we were able to move faster to disburse the e-Penjana funds. We had built the infrastructure to scale digital subsidies nationally from e-Tunai. Our platforms could check against government records to ensure that the money was going to eligible and verified Malaysians and cut out the possibility of duplicate payments across the three wallets.

Moving to digital platforms in the Philippines and Singapore

In the Philippines, the pandemic has hit jobs in some sectors particularly hard. We are partnering with four cities in the national capital region of Metro Manila, to provide livelihood opportunities to street vendors, tricycle drivers, and those affected in the construction and hospitality sectors. Across Manila, Quezon City, Muntinlupa and Navotas, we are supporting the government’s initiative to retrain and bring on people as delivery partners on the Grab platform. As of April 2021, 4,321 people have joined us.

Part of the challenge here for both the government and Grab was to onboard them in the midst of a lockdown. Our Grab Driver Centres didn’t have enough space to cater to the social distancing requirements. We also could not expect potential partners to be able to do it fully online as many do not have access to reliable internet or a laptop to upload documents.

In the end, a combination of online and offline solutions helped. We worked with the local governments to set up dedicated venues to facilitate onboarding in-person with social distancing rules. Grab supplied devices to help partners with onboarding. The local governments got the word out on social media and invited residents to sign up.

We were able to provide training to help partners adapt to working with digital tools. Meanwhile, the local governments provided cross-boundary travel permits and secured work permits so that partners were able to move around safely while the cities were locked down.

Meanwhile, in Singapore, the government was encouraging food and beverage merchants to start selling online, as foot traffic was slashed during a two-month lockdown last year. Smaller, more traditional businesses like hawker center sellers were disproportionately affected by the pandemic. Many did not have any online presence and were not familiar with digital tools.

Grab had a deliberate approach to help them beyond simply getting them to join our food delivery platform, with guidance from the National Environmental Agency, which oversees hawkers, and Enterprise Singapore, which supports local SMEs in their digitalization efforts.

We saw that hawkers had three specific barriers to selling on digital platforms like Grab’s: the usual commission rates we charged would not be feasible for them as they have low margins and smaller average order values; they were not familiar with digital solutions; and it was difficult for individual hawker sellers to standout in an online marketplace.

To address these problems, we created a unique mix-and-match model that allowed people to order food from multiple stalls in a hawker center under a single delivery fee, with reduced commission fees charged to each seller. We offered training for stall operators, many of whom are elderly, to get familiar with our app.

This made the economics of online delivery work for both the sellers and buyers, by keeping costs low. Consumers were attracted to the variety they could get from the entire hawker center, which gave greater visibility to the unique products offered by each seller. As temporary relief during the latest dining-in restrictions, Grab and the Singapore government pitched in to ensure hawker centers do not get charged commission for orders through Grab from 16 May to 15 June 2021.

We iterated on a number of approaches to find a model that was the most cost-sustainable for both Grab and the hawkers. This has allowed us to expand the initial pilot in one hawker center to support close to 400 hawkers in 50 hawker centers, since May 2020, covering 44% of the government-run hawker centers in Singapore.

We have gained valuable experience and lessons through these partnerships. From hawker sellers and tricycle drivers, we learned to understand unique needs and use technology as a tool to create bespoke models. From Malaysians, we saw how preparation and awareness is crucial to build trust in digital tools in times of crisis. In Indonesia, we learned to combine technology with local creativity. Their support and trust makes our work possible.

Ming Maa is the president of Grab.