Bridging Borders for a Cleaner Future: ASEAN’s Next Leap in Cross-Border Power Trade

Senior Consultant on Energy Policy, Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia

Director for Energy Policy and Head of Asia Zero Emission Center, Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia

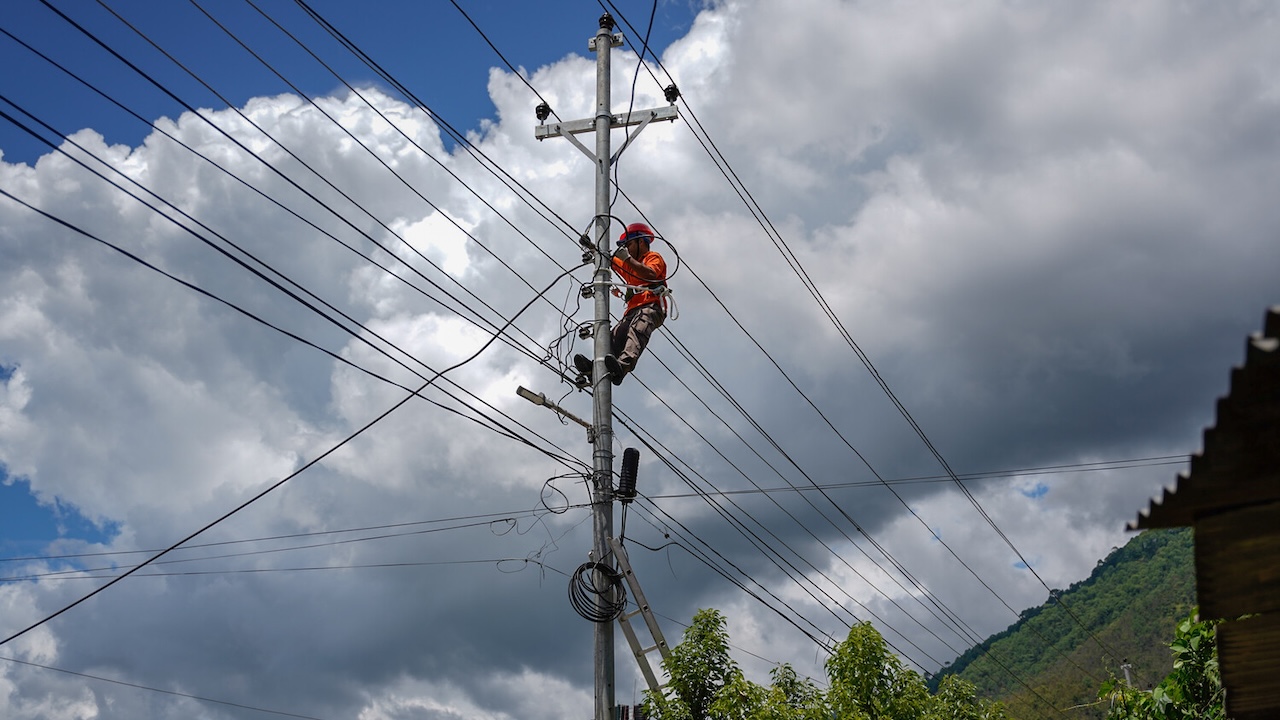

Across ASEAN, electricity demand is set to almost double by 2040, driven by economic growth, industrialization, and urbanization. Photo credit: ADB.

In today’s world, energy security is no longer just about having enough fuel within one’s borders—it is about building systems that are interconnected, resilient, and low-carbon.

This article is published in collaboration with the Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia.

In Southeast Asia’s race toward a low-carbon future, no country can afford to go it alone. The region’s geography, uneven resource distribution, and diverse market structures make collaboration not just beneficial but essential. In today’s world, energy security is no longer just about having enough fuel within one’s borders—it is about building systems that are interconnected, resilient, and low-carbon.

A flagship example is the Lao People's Democratic Republic–Thailand–Malaysia–Singapore Power Integration Project (LTMS-PIP), ASEAN’s first successful multilateral cross-border electricity trade, launched in June 2022.

For Singapore, the LTMS-PIP was a breakthrough—importing renewable electricity from a neighboring region for the first time. It proved that clean power trade across multiple national borders is not only possible but practical, something that seemed politically and technically unlikely just a few years ago. Yet, while this project is a landmark, it also underlines the scale of the challenge if ASEAN is to make large-scale clean energy exchange a cornerstone of its power sector.

Singapore’s limitations are stark: scarce land, no large-scale domestic renewable resources, and a dense urban population. To meet climate targets, maintain competitiveness, and power its fast- growing digital economy—where data center capacity is expected to double within a decade—it must import clean electricity. The LTMS-PIP's 100 megawatts of Lao hydropower, transmitted via Thailand and Malaysia, is a start, but far short of the multi-gigawatt volumes needed to decarbonize the power supply, transport, and heavy industry.

The project has dispelled doubts over technical feasibility, but challenges remain. The scale is still small, trading is fixed under a government-to-government deal rather than through an open market, and infrastructure gaps, mismatched regulations, and non-uniform technical standards continue to slow expansion. Addressing these will require political will, coordinated reforms, technical upgrades, and strong investor confidence.

Across ASEAN, electricity demand is set to almost double by 2040, driven by economic growth, industrialization, and urbanization. At the same time, member states have committed under the ASEAN Plan of Action for Energy Cooperation and the Paris Agreement to ramp up renewable energy. But resources are unevenly spread: hydropower in the Mekong, solar in parts of Indonesia, the Philippines, and Thailand, wind in Viet Nam. Without cross-border trade, such resources remain underutilized while other countries rely heavily on fossil fuels.

During its ASEAN chairmanship in 2025, Malaysia made energy integration a political priority, pushing the ASEAN Power Grid as a flagship initiative. It has promoted harmonized grid codes, transparent trading rules, and financing frameworks for new interconnections—steps aimed at building both infrastructure and the foundation of a regional electricity market.

Malaysia is also moving to become a clean energy exporter, piloting renewable energy schemes for neighbors and combining solar, hydropower, and storage in hybrid generation projects. These efforts align with its national target to boost renewables to 40% of installed capacity by 2035 and cut coal dependence.

Such political momentum is vital. Without strong leadership and trust, regional integration could falter under domestic energy security concerns and competing priorities. Binding frameworks, shared commitments, and willingness to compromise will be key.

Singapore, for its part, is pursuing a multi-pronged approach—exploring imports from Viet Nam, Indonesia, and Cambodia, aiming for 4 gigawatts of low-carbon power by 2035. It is investing in subsea transmission, floating solar, and advanced storage, while advocating for an open, competitive ASEAN electricity market to encourage private investment and accelerate renewables deployment.

The LTMS-PIP offers a clear lesson: decarbonization and energy security can be mutually reinforcing. A well-integrated regional market would enable larger renewable rollouts, balance supply and demand across borders, and reduce over-reliance on any single source. This would lower carbon intensity and costs while making the region more resilient to climate shocks, fuel price swings, or geopolitical risks.

Achieving this vision will take more than cables and substations. It requires flexible market mechanisms, regulatory alignment to give investors certainty, and technical cooperation to ensure grid stability as intermittent renewables expand.

The LTMS-PIP may be modest in size, but it is a vital foundation. ASEAN has a rare chance to turn early progress into a fully interconnected, decarbonised power system. Done right, the ASEAN Power Grid could become both a symbol of cooperation and a pillar of the region’s economic and environmental future.

Electricity is the lifeblood of modern economies. The way ASEAN generates, trades, and consumes will shape the region’s prosperity for decades. By deepening cooperation, harmonizing rules, and investing in cross-border connections, Southeast Asia can ensure its energy transition is greener, more secure, more affordable—and more inclusive.

The LTMS-PIP has shown that bridging borders for a cleaner future is possible. The next step is scaling up, sustaining momentum, and powering ASEAN’s growth through collective action, shared commitment, and partnership.

This article was first written for the Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia and has been published in The Manila Times.

Weerawat Chantanakome

Senior Consultant on Energy Policy, Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East AsiaWeerawat Chantanakome has more than 25 years of experience in energy security and sustainability. He has worked closely with leading international organizations and dialogue partners. He currently serves as an honorary counsellor for the Ministry of Energy of Thailand and is seconded as senior consultant on energy policy at the Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia in Jakarta. Previously, Weerawat was the executive director of the ASEAN Centre for Energy in Jakarta, serving all 10 ASEAN member states.

Nuki Agya Utama

Director for Energy Policy and Head of Asia Zero Emission Center, Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East AsiaNuki Agya Utama is an energy expert currently serving as director for energy policy and head of the Asia Zero Emission Center at the Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia. Previously, he was the executive director of the ASEAN Centre for Energy. He is an expert on renewable energy, energy efficiency, and green design, and holds advisory positions at the Asia Pacific Energy Research Centre and the UN ESCAP. He has a PhD in environment and energy technology.

ERIA (Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia)

ERIA is an international organization that was established in 2008 by an agreement of the leaders of 16 East Asia Summit (EAS) member countries. Its main role is to conduct research and policy analyses to facilitate ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) building and to support wider regional community building.