Safer Trains: Expanding Communication Platforms to Report Gender-Based Violence in Transport Services in the Philippines

Grievance redress mechanisms are essential for quick response to stakeholder feedback—and to make public transport equitable and safer.

Public spaces and transport services should be safe and accessible to all. Unfortunately, women and girls worldwide experience harassment, catcalling, unwanted attention, groping or worse while walking or using public transport.

A 2020 USAID policy brief estimated that public streets and public transportation are the two top places where sexual harassment occurs. Though cases go largely unreported—officially at least—testimonies, many with video and photo evidence, are freely shared on social media where survivors and witnesses could hide behind made-up names and avatars.

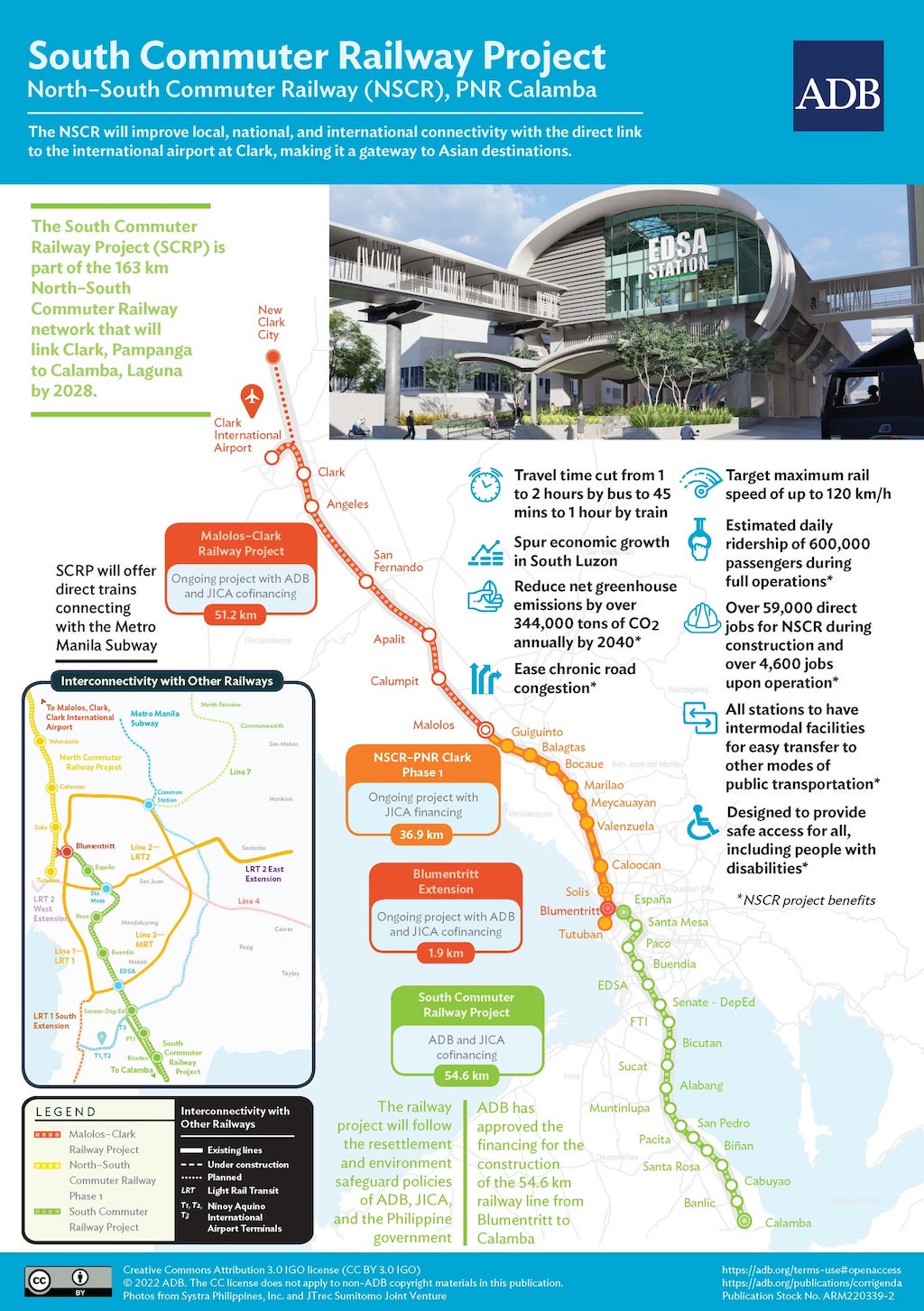

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) supports the Philippine government’s vision to bring back the culture of rail transport in the country through the Malolos-Clark Railway and South Commuter Railway projects. With the projects came the responsibility to also address gender-based violence (GBV) in public transport systems from construction to operations.

Preventing and addressing gender-based violence in grievance redress mechanisms

Since 2019, the Philippines has a policy in place, Republic Act 11313 or the Safe Spaces Act, penalizing sexual harassment in public spaces, including common carriers, public utility vehicles, and private vehicles hired through app-based transport services.

For ADB projects, grievance redress mechanisms (GRM) are essential for quick response to stakeholder feedback—and to make public transportation equitable and safer. For the Malolos-Clark Railway and South Commuter Railway projects, safer means recognizing that GBV exists—on many levels among many groups of people involved in public transport systems at different times.

In 2019, ADB and the Transport Department started to pilot a GRM that integrated GBV in its approaches and typologies for railways projects. Already institutionalized, the GRM covers construction and operations—each with different mechanisms and workstreams, and will also be expanded to cover other public transportation projects.

Case stories among stakeholder groups in Philippine public transport projects

Gina: She welcomed the space to earn more from selling food outside a railway construction camp. The discomfort from inappropriate touching by several workers was a liability in her balance sheet. When they crossed a bottom line, she hurried to the village’s Violence Against Women and Children (VAWC) desk to report the harassment.

Pauleen: She came back exhausted from consultations with families resettled in a housing site. Heading back late in the evening and falling asleep on the car of a transportation support company, she woke up with someone holding her down. She e-mailed a report detailing the abuse.

Doris: Desperate to get home, she braved the crowds and rode the train. She came out traumatized and angry after having been touched. She texted a hotline to report the abuse.

Their stories are cases of key behaviors obtained from consultations—from recognizing GBV to reporting them.

These stories also represent nearly everyone who experienced GBV in public transport projects particularly—villagers near construction sites where railway projects are being built, employees of contractors, transportation department personnel, and commuters.

The critical role of communication in grievance redress mechanisms

Most, if not all, project-level GRM typologies constitute common safeguard-associated concerns—environment, land acquisition and resettlement—and consequently, majority of issues raised are connected to pollution, habitat and livelihood threats, and compensation. With substantive stakeholder feedback, often with detailed documentation of concerns, GRMs have become critical to initiate positive changes in how projects are designed and implemented.

For GBV issues, however, it is more complex. Cases will remain shadowy and secret, statistical and static—unless stakeholders report to trigger response. People targeted by the GRM—villagers in project construction sites, contractors, Transport Department employees and commuters—will not report unless barriers to reporting are identified and removed. People need to:

- Recognize that abuse, exploitation, and harassment are forms of violence

- Know where to report

- Have many options to communicate

- Trust the platforms (respectful of rights to confidentiality and privacy)

- Get information and support after reporting

Recognizing abuse, exploitation, and harassment. Many forms of abuse, exploitation, and harassment have become normalized. Communication is then crucial to make clear that in construction sites, workplaces, and public transport catcalling, unwelcome advances, malicious touching, financial blackmail for sex, cyberbullying—are forms of violence. Once survivors stop tolerating these, they can consider the next step: reporting.

Expanding communication platforms to report gender-based violence

Knowing where to report. The Malolos-Clark Railway project’s communication strategy pointed out that although accessible, existing communication platforms (government helpdesks and hotlines) need expanding to maximize digital channels. The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in GRMs evolving quickly.

Having many options to communicate. An electronic GRM (“eGRM”) that integrates existing mechanisms with web-based reporting has increased options for reporting and allowed confidentiality and options for anonymity when reporting GBV cases. For the Transport Department, the eGRM integrated platform automated manual logging and documenting of complaints into one central database, increasing efficiencies for flagging contractor packages, and for action planning.

Trusting the platform. Integrating GBV in the eGRM, ensuring that the systems are survivor-centered, and increasing reporting behavior required a multi-disciplinary approach and expertise of development communication, gender, safeguards, and IT specialists. Before the eGRM went live, the team set up and trained focal persons in case response and handling, debugging and testing, promoting the eGRM, and ensuring continuity of support through referral to relevant government agencies.

Getting information and support. Referral to ensure the continuum of care for survivors and whistle blowers is critical as some GBV cases may go beyond the mandate and capacity of the Transportation Department or are outside of the project scope, such as handling psycho-social or legal counseling, and providing rescue and safe spaces.

At ADB, we are integrating mechanisms into our projects, including GRMs and communications strategies, that will ensure public transport systems are safe for everyone, and help us avoid, and eventually aim to eliminate, the ordeals of the type Gina, Pauline and Doris faced.

This article was first published by ADB on 25 November 2022.