Assessing the Implementation of Indonesia’s National Nutrition Information System

Research Coordinator, UN Pulse Lab Jakarta

Former Communication Manager, Pulse Lab Jakarta

Using a mixed-methods approach, stakeholders examined how an app that records and reports on community nutritional status can better help health workers do their job. Illustrations courtesy of UN Global Pulse/Swastika Exodian and Lia Purnamasari.

Understanding the experiences of users fills in gaps in implementing an app that records and reports on community nutritional status.

This story is published in collaboration with Pulse Lab Jakarta.

Emerging digital technologies are enabling faster and more efficient data collection on a range of development issues, leading to more timely analysis and action. To support Indonesia's National Movement for Stunting Reduction, the Ministry of Health developed an application for recording and reporting on community nutritional status. Known in short as e-PPGBM or Pencatatan dan Pelaporan Gizi Berbasis Masyarakat Elektronik in Indonesian, this application is designed to identify and monitor nutritional data in a timely, systematic, and sustainable way. With early assessments pointing to challenges in implementing this system, the United Nations Global Pulse through Pulse Lab Jakarta and the government of Indonesia has been collaborating with UNICEF Indonesia and the Indonesian Ministry of Health to gain an in-depth understanding of the implementation gaps.

Reducing implementation gap

The e-PPGBM module is part of a larger nutritional system called SIGIZI, which was designed to aid nutrition-oriented program implementers and policymakers in making informed decisions. Early observations from the Ministry of Health’s Nutrition Surveillance team have revealed issues related to the use of e-PPGBM. These issues range from a lack of clarity in follow-up mechanisms, to inefficient data utilization among the health offices of districts and provinces.

Given the use of e-PPGBM in recording data that can be used to reduce stunting, it is critical to understand the various causes contributing to the suboptimal use of the system. Therefore, our goals were to systematically identify and better understand the gaps in e-PPBGM implementation; identify areas for improvement; and provide recommendations on actions that can be taken to improve optimization of the tool.

To do so, we applied a mixed-methods approach, integrating an online quantitative survey combined with qualitative research using service design principles. By leveraging a service design approach, we are able to methodically organize various components (such as people, technology, and procedures) in order to increase service quality and the user experience. This approach enables a holistic assessment as all parts of the service are examined, from the architecture and supporting infrastructure, to the stakeholders involved (who are critical for ensuring that the service keeps serving the needs of its users).

Understanding the experience of e-PPGBM users

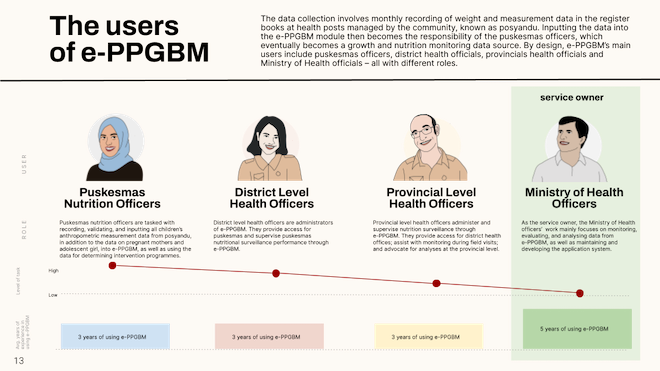

Based on literature review and discussions with relevant stakeholders, we mapped the various user flows. The data collection for e-PPGBM involves monthly measurement and recording weight data in physical registers at health posts managed by the community, known as posyandu. From here, inputting the data into the e-PPGBM module becomes the responsibility of the puskesmas (community health center) officers, which eventually become a growth and nutrition monitoring data source. By design, e-PPGBM’s main users include puskesmas officers, district health officials, provincial health officials, and Ministry of Health officials—all with different roles.

Next, we conducted an online survey involving 1,677 survey respondents from puskesmas, as well as district and provincial health offices. The responses indicated that most users of e-PPGBM find the system to be a helpful resource in assisting them to complete their nutritional surveillance tasks. However, there are several limitations preventing them from fully utilizing the system, such as human resources needed to collect and input the data.

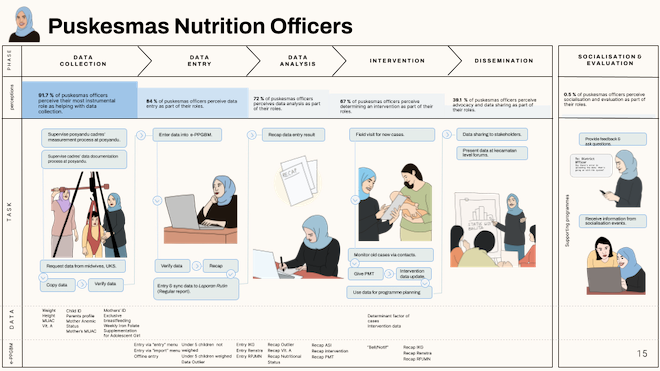

Once the survey results were compiled and analyzed, we conducted a series of in-depth interviews online, coupled with observations at posyandu and puskesmas. To delve into the user experience and the challenges faced by users when utilizing e-PPGBM, we divided the user flow in six phases: 1. Data collection; 2. Data entry; 3. Data analysis; 4. Intervention; 5. Dissemination; and 6. Socialization and evaluation.

With these six phases, we were able to understand in more detail how users interacted with the touchpoints and interface of the e-PPGBM system.

Based on the data collected and synthesized, we unearthed several insights related to the implementation gap of e-PPGBM:

- The design of the e-PPGBM system relies heavily on the puskesmas nutritionists to ensure data is collected and recorded accurately. The system was initially designed to help puskesmas officers collect and report nutritional data more efficiently. However, with limitations related to human resources, capacity, data collection standards, and technology, it has been challenging for puskesmas nutritionists to utilize the system thoroughly, especially for data collection.

- The main challenges with e-PPGBM data entry for puskesmas nutritionists concern inputting large volumes of data each month into an error-prone system. There are volumes of data that need to be inputted into the system each month. Moreover, the system often experiences unexpected errors that cause delays, and for some users the system interface is not intuitive.

- There is a gap between users’ ability to access the data and their ability to leverage it to propose interventions accordingly, which may be described as a data-action gap. The platform does not bridge the data collected with the analysis and insights necessary for users to plan the nutrition-related interventions needed, although there are opportunities to do so.

- The support on e-PPGBM use is still focused on data entry, and its design does not encourage users to report interventions into the system. The reporting of interventions into e-PPGBM is as essential as inputting the nutritional data, whereby the underreporting of interventions could mean inaccuracy in the system’s data.

- There are additional beneficiaries and policymakers who could potentially benefit from e-PPGBM’s data, but concerns about the quality of the data remains an obstacle.

- The socialization and evaluation of e-PPGBM occur regularly; however, the feedback provided on the users’ experiences are rarely translated into improvements.

How do we improve the system and user experience?

Following this service design assessment, we developed several recommendations. These ranged from longer-term steps that can be taken to improve the system, to immediate adjustments that can be made. The longer-term efforts are related to aligning the e-PPGBM system with the Ministry of Health’s recently launched Digital Health Transformation Strategy. Once implemented, this strategy will help address some of the current issues observed with e-PPGBM, such as data standardization, interoperability, and integration of health information systems, especially at the puskesmas level.

In addition, we offered a list of immediate follow-up steps that the e-PPGBM service owners might take. The recommendations include the following:

- Posyandu data recording template: a paper-based standardized template for all posyandu in Indonesia. Having this template throughout all posyandu could help reduce inconsistency about the data collection and recording process at posyandu and puskesmas facilities.

- Image-to-excel converter: a mechanism to convert analog posyandu records into a digital sheet that will enable faster data reporting and entry into e-PPGBM.

- Data anomaly alert function: a feature in e-PPGBM which automatically identifies possible data anomalies once data is entered and directly alerts users. The feature could help reduce the effort needed from puskesmas nutritionists for data verification.

- Recommendation generator: a feature in e-PPGBM that provides detailed recommendations on intervention options once data is entered and analyzed by e-PPGBM.

- Intervention feedback mechanism: this would provide feedback to users once intervention data are recorded into e-PPGBM.

- Moderated Q&A platform: an online bulletin board facilitated by the service owner and provincial government, where users can post questions related to e-PPGBM usage.

Services are co-produced with users

Understanding the experiences of users in employing a service is important, particularly as services are generally co-produced with the users. As a methodology, service design allows us to delve into what may often seem like a complex interaction among various components within a service. It also helps us to understand how the service fits in a larger system—making the invisible visible and showing what is behind the scene as well as on the front and back stages. It is envisaged that the ideas and insights generated from this assessment will help to improve the functionalities of e-PPGBM, improve user experience, and ultimately produce value by aiding nutritionists, health workers, and policy makers in their work.

Puskemas are community health centers, which are open every day.

Posyandu are community-managed health posts usually open once a month with a health program, such as immunization for infants and children.

This research was conducted by UN Global Pulse through Pulse Lab Jakarta’s team, with support from UNICEF Indonesia and the Indonesian Ministry of Health.

This article was first published by Medium on 6 July 2022.

Aaron Situmorang

Research Coordinator, UN Pulse Lab JakartaAs research coordinator at UN Pulse Lab Jakarta, Aaron Situmorang focuses on service design, digital transformation, and future foresights.

Dwayne Carruthers

Former Communication Manager, Pulse Lab JakartaDwayne Carruthers works as the public advocacy manager at UN Global Pulse through Pulse Lab Jakarta, advocating for the adoption and responsible use of data and AI for evidence-based decision-making in the public sector. He is concurrently the global communications lead of the Global South AI4COVID program. His work has focused on exploring the intersection between people and technology, and pulls from his background in journalism, international law, and diplomacy.

UN Global Pulse Asia Pacific Hub

UN Global Pulse is the United Nations Secretary-General’s innovation lab. The Asia Pacific Hub is designed to run portfolios of on-the-ground innovation projects that apply data, digital, foresight and behavioral science methods to regional issues. The hub builds on the successful partnership model that spans over 10 years between the UN and the Government of Indonesia under the Pulse Lab Jakarta portfolio.

Visit our Knowledge Hub at http://knowledgehub.pulselabjakarta.org/.